“Is it worth being a landlord, or should I invest in REITs instead?”

It’s a question many aspiring investors ask when considering real estate. Owning a rental property brings up images of steady rent checks and home value appreciation – but also leaky faucets at 2 AM. On the other hand, REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts) promise a way to invest in real estate without ever fixing a toilet, simply by buying shares on the stock market.

Deciding between buying a physical property or investing in REIT stocks can be confusing. While the stock market’s historical ~10% annual returns have outpaced housing’s typical 4–8% yearly gains , rental properties offer tangible assets, potential monthly income, and hefty tax perks. In this guide, we’ll break down the financials, risks, and lifestyle factors of each approach. By the end, you should have a clearer idea whether being a hands-on landlord or a hands-off REIT investor better suits your goals.

Financial Breakdown: Upfront Costs, Returns, and Cash Flow

Upfront Investment

One major difference is the cash needed to get started. Buying a rental property usually requires a sizable down payment (often 20% of the property price) plus closing costs. For example, a $300,000 rental might demand $60,000 or more upfront, not to mention additional funds for any repairs or improvements before renting. In contrast, investing in a REIT is far more accessible – you can start by purchasing just a single share (sometimes for under $100) or investing through a real estate ETF with even small amounts. There’s no need to qualify for a mortgage or shell out tens of thousands at once; virtually anyone with a brokerage account can get started with minimal capital.

Ongoing Costs

Owning a rental comes with continuous expenses. You’ll pay property taxes (typically 1–2% of the home’s value annually), insurance, and set aside money for maintenance and repairs (commonly estimated at ~1% of property value per year) . If you hire a property manager to handle tenants and maintenance, that’s another ~8–12% of the monthly rent gone to fees . For example, if your property rents for $2,000/month, a management company might take around $200 off the top. Vacancies can also cut into your income – any month without a tenant means covering the mortgage out-of-pocket. REIT investments, on the other hand, have minimal ongoing costs for the investor. There are no property bills for you to pay; management and operational costs are handled by the REIT company.

You might pay a small expense ratio if you invest via a REIT mutual fund or ETF, but many index funds charge under 0.5% (sometimes as low as 0.1% or less) per year , which is trivial compared to the costs of owning property directly. In short, rental owners face multiple bills and possible surprise expenses, whereas REIT investors have virtually none of these headaches (the REIT company takes on those costs).

Cash Flow and Returns

A well-chosen rental property can provide monthly cash flow if the rent collected exceeds all expenses. Let’s say you collect $2,000 in rent and after paying the mortgage, taxes, insurance, and maintenance, you net $300 per month – that’s your cash flow (which you can pocket or reinvest). Over time, you also hope the property value increases (home appreciation) adding to your overall return when you eventually sell. REIT stocks don’t pay monthly income, but most pay quarterly dividends to investors from the rental income they collect on their portfolio of properties. Yields can range widely – on average, REIT dividend yields tend to fall in the lower single digits (often ~3–5% annually), though some higher-yield REITs pay more .

The upside is that REIT share prices can appreciate as well, just like any stock, so your total return is dividend income plus any price gain. Historically, REITs have delivered solid total returns. In fact, over the long run many REITs have matched or beaten the returns of direct real estate. Often, rental property investors might target around an 8–12% annual return on investment when combining cash flow and appreciation . This can be achievable especially if the property is leveraged (bought with a mortgage) and held for many years in a growing market. However, a good chunk of that return is “locked in” the property’s value until you sell or refinance – your annual cash yield might only be a few percent in the early years, with the rest coming as equity growth.

By comparison, the REIT sector’s historical average returns (income + growth) have been on par with stocks. For example, one study found publicly traded REITs returned about ~9.7% annually over 25 years, versus ~7.7% for privately held real estate in the same period . Another analysis found that from 1994–2016, U.S. home prices (excluding rental income) rose about 3.9% per year on average, while equity REITs delivered roughly 12.6% per year . Clearly, REITs can be very lucrative over time. But remember that those higher returns come with different risks, which we’ll discuss shortly.

To summarize the financial differences, here’s a quick breakdown:

- Rental Property – Upfront: High (down payment + closing costs). Ongoing: taxes, insurance, maintenance, possible HOA and management fees. Cash flow: Monthly rent (potentially a few hundred dollars net per month per property, if managed well). Total returns: Could be 5–10%+ annually (or more) over the long term, especially if property values rise, but varies widely by market and management.

- REIT Stocks – Upfront: Very low (cost of a share). Ongoing: Negligible direct costs (small fund fees, if any). Cash flow: Quarterly dividends (yields often ~3–5%, though some pay higher). Total returns: Historically ~8–12% annually when including price gains , with wide variation depending on the specific REIT and market conditions.

Risk Factors: Volatility, Liquidity, and Tenant Troubles

No investment is without risk, but the types of risk differ between rental properties and REITs.

Market Volatility

If you’ve ever checked stock prices, you know they bounce up and down daily. REIT stocks are no exception – they trade on exchanges and can be as volatile as the broader market. In a bad month or during an economic scare, REIT prices can drop sharply. For instance, early in the COVID-19 pandemic, the stock market (S&P 500) plunged over 30% in just weeks, while U.S. housing prices barely budged (home values dipped only ~3.4% in the same early 2020 period) . Publicly traded REITs felt that stock market pain too – many REIT share prices fell 30–40% in March 2020 before recovering.

In contrast, direct real estate prices tend to move more slowly. Your house doesn’t get “priced” by the market every day, so values are less jittery in the short term. During the 2007–2009 financial crisis, home prices did crash significantly, but it happened over a couple of years, not overnight. According to the Case-Shiller Home Price Index, U.S. housing values fell about 33% peak-to-trough from 2006 to 2011 . By comparison, REITs (and stocks in general) saw much faster and deeper drops in the worst single years (the REIT index lost roughly 37% in 2008 alone, then rebounded strongly in 2009). The bottom line: REITs are more liquid and respond quickly to economic news (for better or worse), whereas real estate is less liquid and more stable month-to-month but can still decline in a prolonged downturn.

Liquidity

One person’s volatility is another’s liquidity. Having an asset you can sell quickly is a double-edged sword. With REITs, if you need cash, you can sell your shares in seconds during market hours – there’s usually a buyer available. With a rental property, selling can take weeks or (more likely) months, involve realtor commissions (~6% of the sale price), closing costs, and a lot of paperwork. You can’t just sell a part of your house to raise a little cash – it’s all or nothing (unless you pursue a cash-out refinance or home equity loan, which adds debt). This illiquidity means real estate is a long-term commitment. You shouldn’t buy a rental if you might need that capital back soon. REITs offer far more flexibility; you can rebalance or cash out of your real estate investment easily if circumstances change.

Tenant & Property Risks

Owning a rental means dealing with real-world issues: tenants who may pay late (or not at all), potential damage to the property, and general wear-and-tear. There’s always the risk of a vacancy – you might go a month or several without rental income while still having to pay the mortgage and bills. On top of that, unexpected repairs can pop up at the worst times (the HVAC can die in the middle of summer or the roof might start leaking during a storm). A single large expense – like a $5,000 air conditioning unit replacement – can wipe out months of profits.

Being a landlord concentrates risk in one property (or a few properties), usually in the same area, so local economic downturns or disasters (e.g. a regional factory closing affecting jobs, or a hurricane) can hit your investment hard. By contrast, a REIT typically owns dozens or hundreds of properties across many regions, diluting the impact of any one tenant or one property’s issues. If a couple of tenants in a REIT’s portfolio default on their leases, it’s a blip in a much larger income stream; if your only tenant stops paying rent, your income goes to zero until you fix the situation. In short, rental ownership carries more idiosyncratic risk – you’re betting on one address and its occupants – whereas REITs give you built-in diversification.

Economic & Interest Rate Risk

Both rentals and REITs are subject to broader economic forces. When the economy is strong and jobs are plentiful, you’ll likely have an easier time finding tenants and can even raise rents. REITs in a strong economy usually perform well too, as higher occupancy and rent growth boost their profits. In a recession, landlords might face more vacancies or pressured rents, while REIT stocks could drop due to market pessimism even if their properties continue to produce income. Interest rates play a big role as well.

Mortgage rates affect rental investors directly – if rates rise, buying or refinancing property becomes more expensive, and high rates can soften housing prices in general. REITs are also sensitive to interest rates: when rates climb, income-focused investors sometimes rotate out of REITs (viewing bonds or savings accounts as safer yield alternatives), and higher interest expenses can cut into REIT profits if they carry a lot of debt. We saw this in 2022–2023 when interest rates spiked; many REITs saw their stock prices dip 20% or more as investors recalibrated. However, real estate (both physical and REIT-owned) can also act as an inflation hedge – property values and rents often rise when inflation rises, providing some protection that many fixed-income investments lack.

In terms of historical risk/return trade-off, owning real estate directly has meant lower volatility but also lower average returns, whereas REITs had higher long-term returns but rockier rides year to year. Over one 23-year analysis, privately owned homes had about 5 losing years (most declines were very modest, around -3% on average in those down years), while REITs had 4 losing years but with much sharper average drops (nearly -19% in down years) . This highlights that REIT investors must stomach stock-like swings, whereas landlords deal with more gradual value changes but potentially high personal stress when things go wrong (like a nightmare tenant or a market crash that leaves you “underwater” on your mortgage).

Passive vs. Active Investing: How Much Effort Do You Want to Put In?

Another huge difference between buying rentals and buying REITs is the level of involvement required. In simple terms, being a landlord is often an active investment – almost a part-time job – while investing in REITs is mostly passive.

Being a Landlord (Active)

When you own and manage a rental property, you’re not just investing money; you’re investing your time and labor as well. You’ll need to advertise and show the property, vet and select tenants (which might involve credit checks and references), handle lease agreements, and be on call for maintenance issues. If the tenant calls at 8 PM on a Friday about a broken pipe, guess who’s responsible for getting it fixed? Even if you don’t swing the hammer yourself, you’ll be arranging a plumber and likely footing the bill. Some landlords relish the involvement – you have full control, can personally ensure the property is well-kept, and can form a relationship with your tenants. But it’s not truly passive income when you’re the one scheduling repairs and ensuring rent is paid.

Many new landlords are surprised at how much work can be involved: dealing with late payments or enforcing rules, gardening or snow removal (if not delegated to the tenant), regular checks on the property’s condition, and of course the paperwork come tax time (tracking all your expenses, depreciation schedules, etc.). You can hire a property manager to outsource a lot of this work, but as mentioned, that might cost around 10% of your rent each month , which eats into your returns. And even with a manager, as the owner you may still need to make big decisions or approve repairs. In essence, owning rental property is more like running a small business – you’re actively involved in operations, or at least overseeing them.

Investing in REITs (Passive)

Buying shares in a REIT is as easy as buying any stock – once you’ve made the purchase, your job is essentially done. You don’t need to worry about individual tenants, leaking roofs, or any day-to-day management.

The REIT’s professional management team handles acquiring properties, signing up tenants, maintenance, and all the operational headaches for you. You can literally be making money from real estate while you sleep, or while you’re on vacation, with no more effort than it takes to log in and check your brokerage account. This hands-off nature makes REITs attractive to those who want exposure to real estate without the time commitment. It’s true “passive income” in that sense – you collect dividend checks (or reinvest them) and let someone else deal with the late-night tenant calls. One way to think about it: Owning a REIT is like owning a tiny slice of thousands of rental properties across the country, but you don’t have to manage any of them.

That said, being passive means less control. You can’t decide to renovate a building or raise rents on a particular tenant – those decisions are made by the REIT’s management. And you’re trusting that management to do a good job; poor management decisions or market missteps can hurt the REIT’s performance, and you as a shareholder have little direct say (aside from voting on broad corporate matters occasionally). But for many, the trade-off is worth it. If you have a full-time job or simply don’t want a second job managing properties, REITs let you invest in real estate with zero effort beyond the initial research and purchase.

Lifestyle Considerations

Being a landlord can be rewarding if you enjoy real estate, don’t mind occasional hands-on work, and like the idea of personally building something (some people take pride in improving a property and providing a home for tenants). It can also be stressful and inconvenient at times. REIT investing, meanwhile, is ideal for those who prefer a set-it-and-forget-it approach, or who want real estate exposure but also want to keep their life flexible (no need to stay local to manage a property – your REIT investments move with you). There’s also a middle ground: some investors hire property management for their rentals to make them more passive; just remember, this reduces your income and you still bear the ultimate responsibility if big issues arise.

In summary, ask yourself how much time and energy you’re willing to devote. If you love being involved and see yourself actively managing a portfolio of homes, the landlord route could be fulfilling. If you’d rather invest with a few clicks and then get back to your day, REITs fit that bill.

Tax Considerations

Taxes can significantly impact your net returns, and they work quite differently for rental properties vs. REIT investments. Both have some advantages and drawbacks in the tax department.

Rental Property Taxes

Owning real estate directly comes with some of the best tax benefits available to investors. Rental income is generally taxable, but the tax code allows you to offset a lot of that income with related expenses. You can deduct mortgage interest, property taxes, insurance premiums, maintenance and repair costs, professional services, and other expenses against your rental income. Perhaps the biggest benefit is depreciation: the IRS lets you deduct a portion of the property’s value each year as a paper expense (even if the property is actually appreciating!).

Residential rental property can be depreciated over 27.5 years – so if the home (excluding land value) is worth $275,000, you could write off about $10,000 per year as depreciation expense. This often means that on paper your rental “profit” is much lower than your actual cash flow, sometimes even zero or a loss, which reduces your current taxes significantly. Many rental property owners pay little to no tax on their rental income because of depreciation and other write-offs . Additionally, when it comes time to sell, homeowners have a special exclusion (up to $250k of capital gains tax-free if it was your primary home, or $500k for a married couple, provided you lived in it for a couple years).

While that exclusion doesn’t directly apply to a pure rental property (since it’s not your primary residence), real estate investors have another trick: the 1031 exchange. A 1031 exchange lets you sell an investment property and reinvest the proceeds into another property without paying capital gains tax at the time of sale – effectively deferring the tax indefinitely.

This is a powerful tool to “trade up” properties over time without losing a chunk of your profit to taxes each sale. Do note, however, that depreciation you claimed gets recaptured (taxed) when you sell if you don’t do a 1031 exchange, and rental income (after expenses) is taxed as ordinary income. Still, between deductible expenses, depreciation, and strategies like 1031 exchanges, the tax code for landlords is very friendly. You can even deduct travel to and from your property for management, home office expenses if you run your rental business from home, and more (always consult a tax advisor to do this properly).

REIT Taxes

REITs have their own set of rules. By law, a REIT must pay out at least 90% of its taxable income as dividends to shareholders. In exchange for doing so, the REIT itself pays no corporate income tax (a big reason REITs exist – they’re pass-through entities). However, that means the tax burden is shifted to you, the investor, when you receive those dividends. And unlike typical stock dividends, which often qualify for lower capital gains tax rates, REIT dividends are usually taxed as ordinary income in your hands . In practical terms, that means if you’re in, say, the 24% income tax bracket, your REIT dividend is taxed at 24% (whereas a qualified dividend from a regular company might be taxed at 15% or 20% capital gains rate). This higher taxation on dividends is somewhat of a downside to REIT investing in a taxable account.

The good news is, recent tax law changes have given REIT investors a bit of a break: under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (2018), most individuals can deduct 20% of their REIT dividend income off the top before paying taxes on it . Effectively, that means only 80% of the REIT dividend is taxed as ordinary income. For example, if you received $1,000 in REIT dividends this year, you might be able to deduct $200 and only pay tax on $800. This is due to the qualified business income (QBI) deduction, and REIT dividends are included as eligible for it.

Keep in mind this provision is currently set to expire in 2025 unless extended by Congress. Another way REIT investors mitigate taxes is by holding REITs in tax-advantaged accounts like an IRA or 401(k). If you hold REIT funds in a Roth IRA, for instance, you pay no tax on the dividends at all (they grow tax-free), and in a traditional IRA/401k, you defer taxes on those dividends until withdrawal. This can make a huge difference over time. Lastly, when you sell REIT shares, any price appreciation is taxed as a capital gain (long-term capital gains rates if you held over a year, which are lower than ordinary income rates). Meanwhile, when you sell a rental property, your profit is subject to capital gains tax too (with no special low rate unless it was your personal residence) and depreciation recapture tax, unless you do a 1031 exchange.

Summary of Tax Pros/Cons

Rental properties allow you to shelter a lot of income via depreciation and expenses – potentially making the investment very tax-efficient (especially if you’re in a high bracket and can use paper losses to offset other passive income). You also have strategies like 1031 exchanges to keep deferring gains. The downside is when you do eventually sell without an exchange, you could face a hefty tax bill (including depreciation recapture). With REITs, you don’t get to write off expenses (the REIT company does that), and dividends can be tax-inefficient in a regular account since they’re taxed as ordinary income . But you can avoid most of that issue by using retirement accounts, and you do get a 20% QBI deduction on REIT dividends under current law , which softens the blow.

In short: if you’re looking for ongoing tax sheltering, rental ownership has more levers to pull. If you’re investing in REITs, consider doing so in tax-advantaged accounts or be prepared for the tax bite on those dividends.

(Tax law is complex, so be sure to consult with a tax professional about your specific situation.)

Market Trends & Performance: Past Results and Future Outlook

How have rental properties and REITs performed historically, and what trends might affect them going forward? Let’s take a look at some data and real-world trends:

Historical Returns

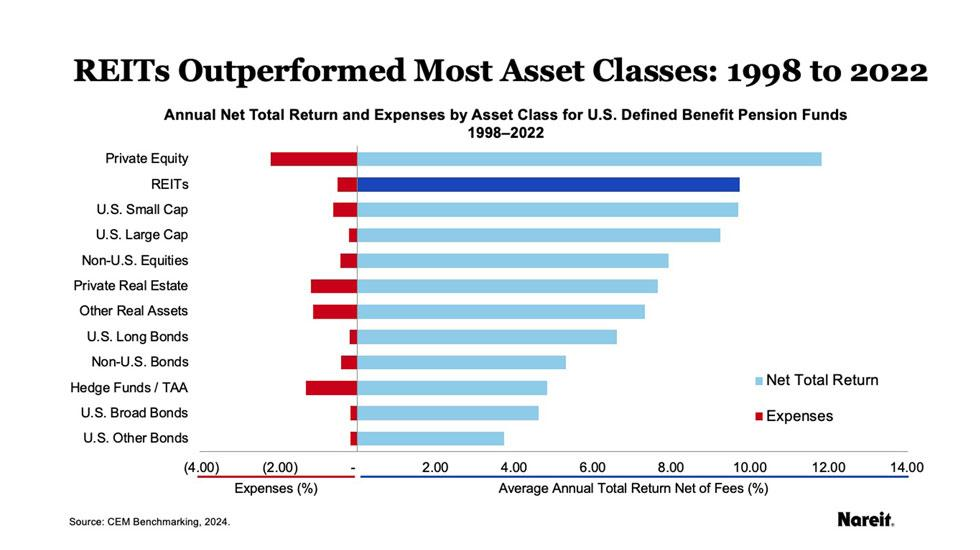

The chart above compares average annual returns for different asset classes over a recent 25-year period (1998–2022). Publicly traded REITs (blue bar) delivered one of the highest returns, nearly on par with private equity, and noticeably above private real estate (light blue bar) . In numbers, REITs averaged about 9.7% net yearly return, whereas privately held real estate (like direct property investments) averaged around 7.7% . This isn’t to say REITs always beat rentals – but over the long haul, REITs have been very competitive, thanks to professional management, portfolio diversification, and perhaps the ability to capitalize on opportunities quickly.

Direct real estate tends to appreciate steadily but slowly, roughly tracking inflation plus a bit more in many markets. For example, over decades, U.S. home prices nationally have grown on the order of 4–5% per year (though this can vary greatly by region and timeframe). Add in rental income, and a landlord’s total return might reach high single digits annually, which is nothing to sneeze at. But REITs, which benefit from both property appreciation and the efficiency of public markets, have historically turned in double-digit annual total returns in many periods. To illustrate, consider the period from the mid-1990s to mid-2010s: one study found equity REITs returned ~12.6% annually on average, handily outperforming the ~3.9% annual home price growth (excluding rents) over the same timeframe . Of course, that was a particular slice of history that included a huge REIT boom in the 2000s.

If we look at more recent times, the picture is a bit more mixed: in the 2010s, many housing markets saw accelerating price gains (especially post-2015), and certain cities had annual appreciation over 10%. Meanwhile, REITs had some great years and some weaker ones (e.g., 2018 was a down year, 2019 was strong, 2020 saw a sharp drop then recovery).

During Crises

Both asset classes have gone through tests. The 2008 housing bust was arguably worse for direct homeowners – prices dropped significantly and took years to recover in many regions. REITs were hammered initially (some lost over 70% of their value from peak to trough around 2008–09) but then rebounded strongly as the economy recovered and investors hunted for bargains. By 2010 and 2011, many REITs had regained a lot of ground, while housing was still near the bottom. On the flip side, the 2020 pandemic caused a short, sharp recession: housing held up remarkably well (after a brief pause, home prices surged as demand outstripped supply), whereas some REIT sectors (like retail and office REITs) struggled due to shutdowns and work-from-home trends.

REIT performance can also vary greatly by sector: for instance, over the past decade, industrial REITs (owning warehouses and logistics centers) and data center REITs profited enormously from e-commerce and the digital economy – some delivered 15%+ annual returns. Meanwhile, older sectors like office REITs have faced challenges (and were hit hard again by the shift to remote work, with high vacancies in some cities’ office buildings). Residential REITs (apartments and single-family home rental companies) have generally done well as demand for housing stays strong; some top-performing residential REITs even beat the S&P 500 over the last ten years with total returns in the high teens percentage .

Current Market Conditions

As of the mid-2020s, real estate markets are influenced by rising interest rates and a post-pandemic economic landscape. Many housing markets saw record price increases during 2020–2022 due to low interest rates and shifting housing preferences. By 2023–2024, with higher mortgage rates, some markets cooled off or saw slight declines, while others remained resilient due to low inventory. Investors considering rental properties now have to factor in the higher cost of borrowing (a 7% mortgage significantly impacts cash flow compared to a 3% mortgage).

REIT stocks in recent years have experienced volatility – they surged in 2021 (as the economy bounced back), but many lagged in 2022 when interest rates jumped and recession fears loomed. Going forward, a key trend is the sector differentiation: for example, warehouse/logistics REITs (like those owning Amazon distribution centers) may continue to see strong demand, whereas office REITs might face longer-term challenges if remote/hybrid work becomes permanent for many companies.

Retail REITs (malls and shopping centers) are adapting to e-commerce by diversifying tenants and using spaces in creative ways (entertainment, dining, etc.), and the best located shopping centers are still doing well. Residential REITs could benefit from housing affordability issues – as some people get priced out of homeownership due to high rates and prices, demand for rentals (and thus well-located apartment communities) stays high. Healthcare REITs (owning medical office buildings, hospitals, senior housing) are tied to demographic trends like aging populations, which suggest growing need for their facilities, but also must navigate government reimbursement and health crises.

What to Expect

If history is any guide, over the long run both rentals and REITs will provide competitive returns, with REITs potentially on average a bit higher but with more ups and downs. Real estate in general tends to roughly track economic growth and inflation – meaning it won’t likely make you rich overnight, but it can steadily build wealth. Pay attention to interest rates: a falling rate environment generally boosts both home values and REIT prices (since borrowing is cheaper and yields elsewhere are lower).

Conversely, rising rates can put a damper on both. Economic growth and employment are also key: if the economy is adding jobs and wages are growing, people form households and need space, benefiting landlords and REITs alike. If we hit a recession, expect some short-term pain: REIT stock prices could drop, and landlords might see higher vacancy or need to be more flexible on rent. However, real estate has shown resilience – over multi-decade periods, it has almost always trended upward in value. As the saying goes, “They’re not making any more land,” and owning either physical property or shares in property via a REIT is fundamentally about holding a real, tangible asset that people need.

Alternatives in Real Estate Investing

Thus far we’ve compared directly owning rental properties to investing in publicly traded REITs. Those aren’t the only ways to invest in real estate, though. Depending on your goals, there are a few alternative approaches worth mentioning.

Real Estate ETFs & Mutual Funds

These are basically baskets of REITs or real estate stocks packaged into a single investment. For example, the Vanguard Real Estate ETF (VNQ) gives exposure to a broad index of U.S. REITs. By buying one share of an ETF like this, you instantly invest in hundreds of properties across different sectors (office, residential, industrial, etc.) since the ETF holds many REIT companies. Funds offer easy diversification and are just as liquid as any stock. They’re a great option if you want to simplify your REIT investing or reduce risk by holding a broad portfolio rather than picking individual stocks. The trade-off is you won’t get the thrill of choosing a specific REIT that might outperform, but you also won’t suffer as much if one REIT implodes, since it’s a small part of the fund.

Public Non-Traded REITs

These are REITs that are registered with the SEC and operate similarly to regular REITs, but their shares don’t trade on an exchange. You might find these offered by brokers or financial advisors. They still must pay out 90% of income as dividends. The advantage touted is often lower volatility (since shares aren’t trading daily) and sometimes lower correlation to stock market movements. However, they can be illiquid – often you can only redeem shares at certain times or under certain conditions – and fees can be higher or more opaque. Due diligence is needed, as some non-traded REITs in the past had hefty upfront fees.

There are private real estate funds or syndications that pool money to invest in properties, without being publicly traded at all. For instance, a group might raise capital to buy an apartment complex and you can buy a membership/unit in that LLC or fund. Platforms now exist (like CrowdStreet, EquityMultiple, etc.) that allow accredited investors to join specific property deals. These can offer targeted opportunities (say, a new development in a growing city) and sometimes higher projected returns, but usually require you to lock in your money for years and carry more risk (development risk, sponsor risk).

Real estate crowdfunding platforms have emerged to open up these private deals to more investors, sometimes with minimums as low as $500 or $1,000. Some platforms (e.g., Fundrise) offer eREITs – essentially a private REIT that you can buy into for a few hundred dollars, which then invests in a portfolio of real estate projects. These options can be a middle ground between REITs and direct ownership: you get exposure to actual properties and sometimes higher income, but you lose liquidity and have to trust the platform managers.

Fractional Ownership & Tokenized Real Estate

A newer trend is buying fractional shares of individual properties. Some startups allow investors to buy, say, 1/100th of a rental home and receive 1/100th of the rent. This is facilitated through online platforms and sometimes even through blockchain tokenization of property ownership. While still an emerging space, it basically lets you emulate being a landlord (you’re on title as a partial owner) with a very small stake. You get proportional income and can share in value gains. The pros are low minimums and picking specific properties; the cons are very limited liquidity (often you can only sell your fraction on a secondary market if buyers are available) and the novelty/uncertainty of the model.

Real Estate Development or Flipping

Not exactly an “investment product” like the above, but worth mentioning: some people actively invest by flipping houses or developing properties. This is an active, business-like investment more than a passive one, but it is another way to invest in real estate besides being a long-term landlord. Flipping can yield quick profits but carries high risk and tax consequences if not done carefully (profits are taxed as ordinary income if the property was held <1 year, and the work involved is significant). Development can generate large returns if you add value by building or renovating, but again it requires expertise and isn’t passive.

In summary, if neither being a landlord nor buying a REIT quite fits your style, these alternatives provide other avenues to explore. Some are more passive (funds, crowdfunding REITs) and some more active (flipping, syndications where you might have to be involved or at least commit capital for long periods). Each comes with its own risk/return profile and due diligence requirements. The good news is, today’s investors have more options than ever to get into real estate with various levels of capital and effort.

Top REIT Picks for Income and Growth

If you decide that REIT investing aligns better with your goals, the next question is: which REITs should you consider? There are dozens of publicly traded REITs spanning different sectors, each with their own characteristics. Here we highlight a few well-known REITs that are often cited for their strong performance or stability. (These are not personalized investment recommendations, but examples to illustrate the variety of REIT choices. Always do your own research or consult an advisor before investing.)

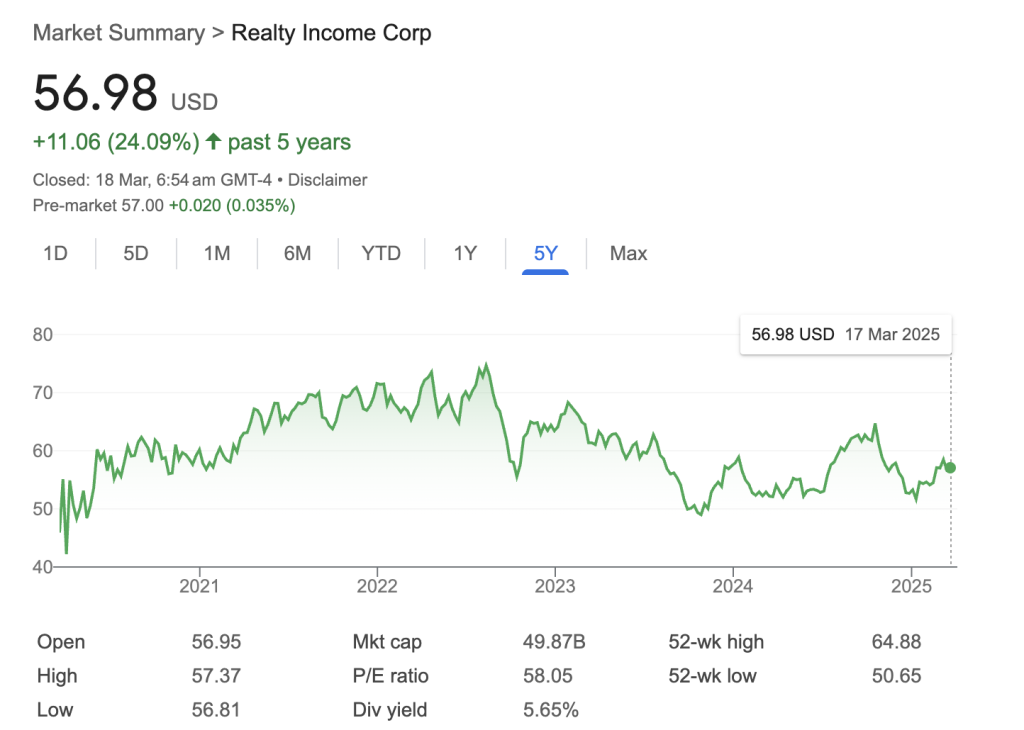

Realty Income (O)

Known as “The Monthly Dividend Company,” Realty Income is one of the most popular REITs for income investors. It owns over 11,000 properties – mostly freestanding retail buildings (think pharmacies like Walgreens, dollar stores, grocery stores, etc.) – leased to tenants under long-term agreements. Realty Income has an exceptional track record: it’s part of the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats, having increased its dividend for 27 consecutive years . In fact, it pays dividends monthly rather than quarterly, which is great for those seeking regular income . With a current dividend yield around 5%, it offers solid income, and its portfolio of high-quality, recession-resistant tenants (like convenience stores, drugstores, and warehouses) has kept occupancy high through various economic cycles. Over the long term, Realty Income has delivered about a mid-single-digit percentage annual dividend growth and respectable total returns. It’s often viewed as a stable, lower-risk REIT choice due to its diversification and track record.

Federal Realty Investment Trust (FRT)

This is another dividend aristocrat in the REIT world. Federal Realty focuses on shopping centers and mixed-use properties in affluent communities. It has one of the longest streaks of annual dividend increases of any REIT – over 50 years of rising dividends (37 years of increases as of a few years ago) , a testament to its stability. FRT’s properties are typically grocery-anchored centers or retail districts that have high foot traffic and demand. While retail has been challenged by e-commerce, Federal Realty’s strategy of owning well-located, necessity-based centers (places people go for groceries, dining, and services) has kept it resilient. Its dividend yield is usually in the 4% range. Investors like FRT for its blue-chip status in the REIT space – it’s considered one of the safest REITs due to its conservative management and prime real estate locations.

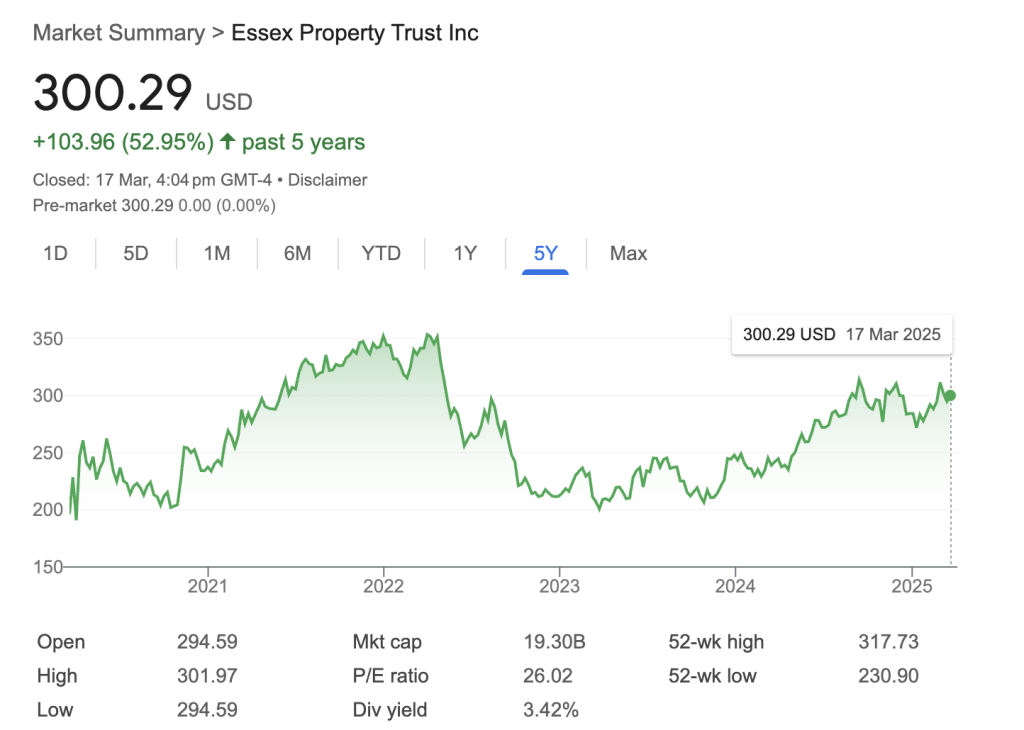

Essex Property Trust (ESS)

Essex is a large residential REIT that owns apartment communities primarily on the West Coast (California and Seattle area). It specializes in high-quality apartments in supply-constrained coastal markets. Essex has increased its dividend every year for 29 years , showing consistency through tech booms, busts, and everything in between. Apartment REITs like Essex tend to benefit from strong rental demand, especially when homeownership is unaffordable for many (as is the case in CA). Essex’s properties often enjoy high occupancy and the company can raise rents over time as demand grows. The trade-off is their markets can be subject to heavy regulation (like rent control laws) and economic swings in industries like tech. But over decades, Essex has proven adept at navigating these and rewarding shareholders. Its current dividend yield is around 3–4%, and it offers a play on long-term housing demand in West Coast employment hubs.

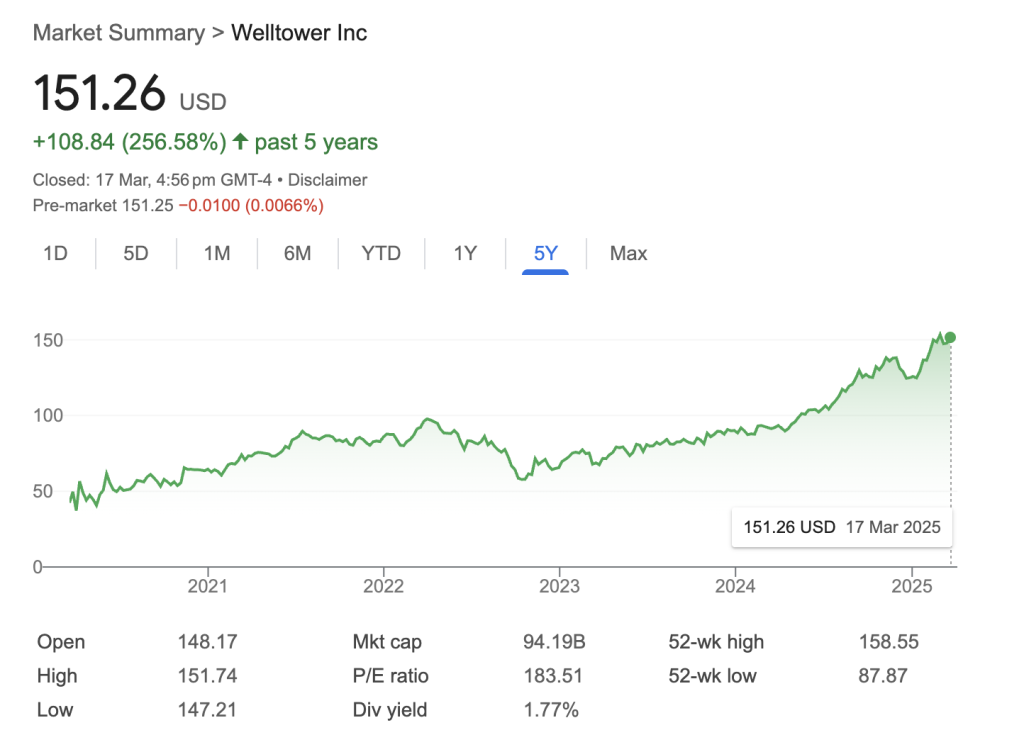

Welltower (WELL)

Representing the healthcare REIT sector, Welltower is one of the largest owners of senior housing, assisted living, and medical office buildings. If you believe in demographic trends (aging Baby Boomers, greater healthcare needs), healthcare REITs like Welltower are compelling. Welltower went through a tough period during COVID-19 (senior housing had extra challenges during the pandemic), but has since rebounded in a big way. In fact, over the last year, Welltower’s stock had a total return of about 70% as the senior housing industry recovered and investors anticipated higher occupancy and rents. That huge one-year performance may not be repeated, but it highlights how beaten-down sectors can bounce back. Welltower yields around 3% in dividends currently, and its portfolio is positioned to benefit from the growing 75+ age population in the coming decade. It’s a bit more growth-oriented (don’t expect a 5%+ yield here), but provides diversification into healthcare real estate.

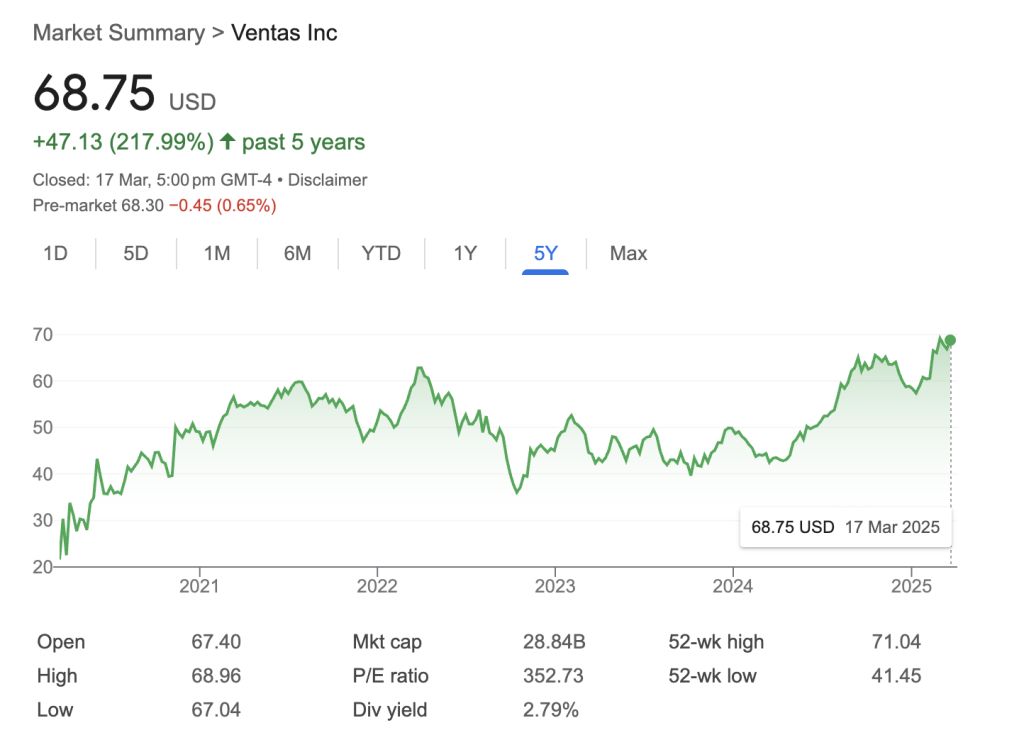

Ventas (VTR)

Another healthcare REIT, Ventas has a mix of senior housing, skilled nursing facilities, and life science campuses. Like Welltower, Ventas had a strong recent run – roughly 68% total return in the past year – after being hit hard in 2020. Ventas is focused on high-quality operators and even has a growing portfolio of research and innovation centers (often partnering with universities for medical research facilities). Its dividend yield is around 3.5%. Ventas and Welltower are often mentioned together as leaders in healthcare REITs. They can add defensiveness (people need healthcare in any economy) and also growth (as demand for senior living rises).

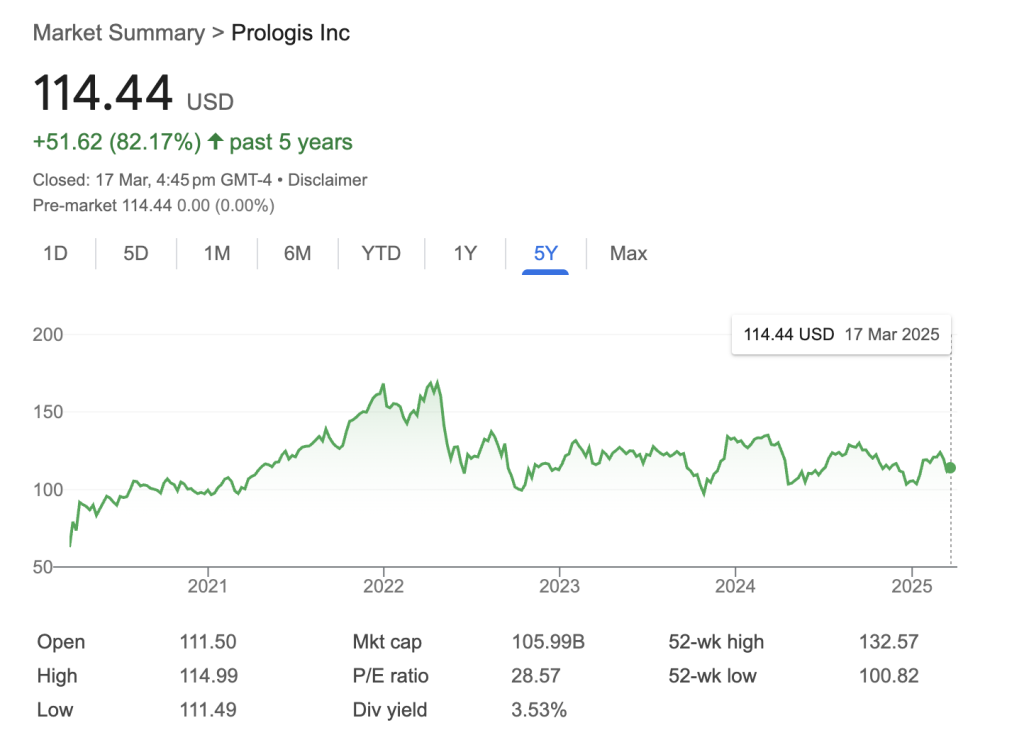

Prologis (PLD)

No list would be complete without the largest REIT by market cap, Prologis. Prologis specializes in industrial real estate, particularly warehouses and distribution centers that are critical for e-commerce and supply chains. It counts companies like Amazon, FedEx, and Home Depot as major tenants. Prologis has been a growth juggernaut – as online shopping boomed, demand for warehouse space surged. The company has achieved high occupancy and rent growth, and expanded globally. While its dividend yield is lower (around 2.8%), it has grown that dividend at a healthy clip and delivered strong capital appreciation (Prologis’ total return was reportedly over 270% for the decade ending around 2022) . For investors looking for a growth-oriented REIT in a thriving sector, Prologis is often a top pick.

These examples just scratch the surface. Other notable names include American Tower (AMT) and Crown Castle (CCI) – unique REITs that own cell tower infrastructure (benefiting from the explosion of mobile data and 5G). Public Storage (PSA) – the leading self-storage REIT, which has proven that people always need storage, especially in times of moving or life transitions (self-storage has had surprisingly strong returns historically). Simon Property Group (SPG) – the largest mall owner, a bit more risky given retail trends, but owning trophy malls that continue to attract shoppers and high-end retailers. And beyond individual companies, remember you can opt for a REIT index fund like the VNQ ETF mentioned, to get a bit of everything.

When evaluating REITs, look at factors like the sector outlook, dividend track record, current yield, and the balance sheet (REITs do use debt, so you want those with reasonable leverage). It’s also worth reading earnings reports or analyst commentary to get a feel for how well management is executing and their strategy for growth.

Final Thoughts: Choosing the Right Path for You

Both rental properties and REIT stocks offer gateways into the lucrative world of real estate. But they cater to different types of investors and lifestyles. There’s no one-size-fits-all answer – the “better” choice depends on your personal situation, financial goals, and temperament.

Ask yourself these key questions as a recap

How hands-on do I want to be?

If you enjoy tangibility and don’t mind (or even enjoy) the work that comes with real estate – finding deals, managing tenants, overseeing renovations – then owning a rental can be both profitable and personally rewarding. You’ll have more control and the potential to use sweat equity to boost returns (e.g., DIY improvements, savvy property management). However, if you prefer a completely passive investment that lets you focus on other things, REITs provide real estate exposure with none of the daily responsibilities.

What is my financial situation and access to capital?

If you have substantial savings for a down payment or access to financing, a rental property might be within reach. But remember to keep a cash reserve for unexpected expenses; real estate is illiquid and cash-intensive. For those without large upfront capital, REITs are an easy entry. You can start with a few hundred dollars or less and scale up over time. You can also dollar-cost average into REIT funds slowly, something not possible with buying properties. Leverage is another consideration: rentals allow you to borrow and potentially amplify returns on your equity (though with risk), whereas REITs typically aren’t bought on margin by most investors (the REIT company itself may use some leverage, but you’re not directly taking a loan).

What are my return expectations and risk tolerance?

If you’re aiming for double-digit returns and don’t mind short-term volatility, REITs have historically delivered that more consistently (especially if dividends are reinvested). They’re subject to market swings, so you have to be okay seeing your portfolio value fluctuate. With rentals, returns can be more stable year-to-year (assuming you have tenants and steady rents), but they might average a bit lower unless you actively improve the property or benefit from strong appreciation. There’s also more “idiosyncratic risk”. One bad tenant or a property-specific issue can drag down your returns. Whereas a bad tenant in one building out of 100 in a REIT won’t move the needle much. Think about whether you’re comfortable tying a lot of money into one or a few properties (concentration risk) or if you’d rather spread it out.

Want to consider hybrid approaches?

It’s not necessarily an either/or choice. Some investors maintain a rental or two for the hands-on experience and steady income, and allocate some of their portfolio to REITs for diversification and truly passive income. This way you get the best of both worlds – the potential high cash-on-cash returns of a rental with leverage, and the hassle-free diversification of REITs. Also, lifecycle matters: maybe when you’re younger with more energy, being a landlord is fine. But later in life you might transition to REITs or real estate funds for simplicity. Real estate can be part of your portfolio in multiple forms.

In conclusion, rental properties vs. REITs is not a battle with a clear winner. But a choice between two different styles of investing in real estate. If you value control, tangible assets, and maximizing tax benefits, and are willing to put in work, being a landlord could be worth it. You might derive satisfaction from building equity in a property you hand-picked and having a say in every decision. On the other hand, if you prefer liquidity, low effort, and instant diversification, REITs are extremely attractive. Through REITs, you can gain exposure to everything from apartments in New York to cell towers and shopping centers with a few clicks, all while collecting regular dividends.

Many successful investors actually do both at different times. What’s important is understanding the trade-offs: time vs. money, risk vs. reward, active business vs. passive investment. By considering the financial breakdown, risks, tax implications, and your own personal preferences, you can make an informed decision. No matter which route you choose, investing in real estate – whether directly or through REITs – can be a powerful way to build wealth and generate income. Good luck, and may your real estate investments (of any kind) prosper!